Archive Volunteer, Philip Milnes-Smith, was part of a fantastic team of volunteers helping our archivist catalogue the Papers of Sir Emery Walker, Engraver, Photographer, Printer, Typographer. The catalogue will be available as a digital resource on this website by the end of 2017, so do keep coming back to visit it. Here Philip writes about some of his fascinating finds.

In December 2016, I started volunteering, one day a week, with The Emery Walker Trust, because experience in the archive sector is a pre-requisite for candidates wishing to study for the professional qualification. Like the other archive volunteers, I have been helping the Archivist, Michele Losse, to catalogue the papers of the following people: Sir Emery Walker himself, his wife Mary Grace Walker, his daughter Dorothy Walker, and her companion Elizabeth de Haas.

When the furniture in the house had been packed up for the restoration, items of correspondence, photographs, notes and other ephemera were separated out and boxed up. However, as most people will realise from their own domestic arrangements, there is some haphazardness to where items are stashed, and totally unrelated things may be tidied away together. Moreover, in this famously Arts and Crafts home, the advice of William Morris about keeping only the useful and the beautiful was, frankly, honoured more in the breach than the observance: distributed among the more significant papers, instructions for long discarded household appliances rub shoulders with old shopping lists, calendars, telephone directories, empty notebooks and advertising leaflets. An important first job when cataloguing was, therefore, to separate out the wheat from this chaff. Then, the items that were left were sorted so that similar items were together (e.g. letters in one folder and photographs in another). When writing up the descriptions of the contents of a specific folder, a balance must be struck between giving sufficient information to assist a future researcher whilst not getting bogged down in excess detail. A final stage of the cataloguing was to select items of greater significance for digitisation, creating both high resolution ‘preservation’ images and lower resolution copies.

In addition to helping secure the history both of the Arts and Crafts Movement, and of the house’s preservation, I have gained some understanding of the individuals who once lived there through studying and cataloguing over 900 items in my time at 7 Hammersmith Terrace.

Mary Grace has probably left the fewest traces, but I have seen evidence not only of her interest in writing poetry, which was sometimes published, but also of her purchasing volumes of contemporary poetry itemised in her account book, and carefully hand-writing knitting patterns, and notes on travelling in warmer climes.

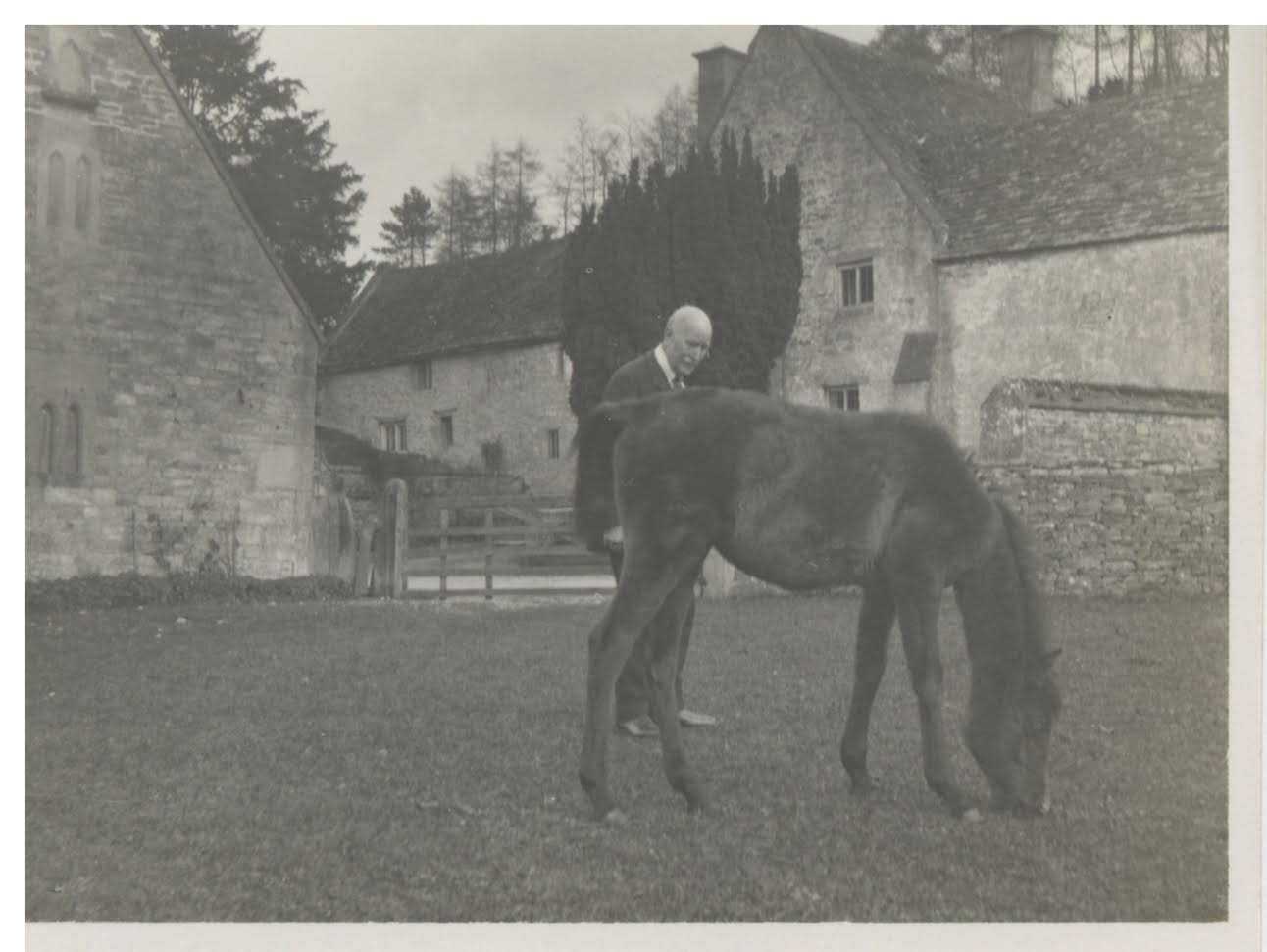

Sir Emery Walker perhaps stands out, in what I have catalogued, more for his antiquarian interests than his professional life, but electrocardiograms hint at his health issues in later life, and I was also intrigued by his investment in the Arabian mares Astola and Aiesha.

Dorothy clearly shared her mother’s enthusiasm for knitting and poetry, and her father’s interest in manuscripts and the art of letter formation. In so many items, from postcards to publication order forms, there are hints of her obsession with Lawrence of Arabia, hero of the age. I liked the glimpse of a (thankfully) bygone age afforded by a letter from the bank to her father informing him of the extent of her overdraft.

Elizabeth de Haas, who also liked to travel, took extensive notes when attending lectures in archaeology by Mortimer Wheeler and Kathleen Kenyon, campaigned tirelessly for the house to be saved, and took an approach to Christmas decoration that was the opposite of minimalist chic! Dorothy and Elizabeth’s intimate messages demonstrate their very close relationship.

However, the letters, postcards, notes and photographs, also reveal the social networks to which these four residents of Hammersmith Terrace belonged. To return to the title quotation, our work helps ensure that these people too will be, in a sense, “alive in the future which we are now helping to make”. Some of their contacts remain household names. George Bernard Shaw, for example, knew the Walkers through a shared interest in Socialism, and was acknowledged as the photographer in several portraits of Dorothy over the years. She had a knitting pattern labelled ‘stockings for GBS’, but sadly his wife, who stated in a letter that, when gardening at Ayot, he always wore gloves Dorothy had made, made no corresponding revelation about the great man’s socks!

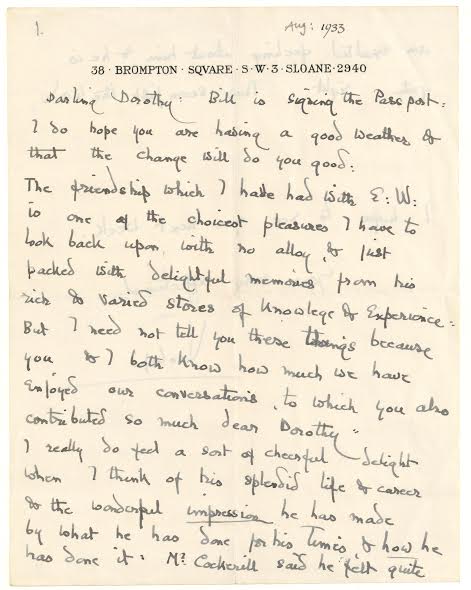

Violet Gordon-Woodhouse, a musician whose extraordinary personal life is worthy of a movie, is less well known, but she seems to have befriended Dorothy after her father’s death. Violet’s finger dimensions were notated by Dorothy to help her knit fitted gloves, and she seems to have created a distinct address book of Violet’s West Country circle. Violet’s death in 1948, marked in the archive by the funeral service booklet, came just months before Elizabeth de Haas was chosen to be Dorothy’s companion.

One of the most satisfying parts of the cataloguing role is confirming the identity of those who signed their letters with just one name, because they were so well known to the addressee. A single letter signed Doris had insufficient clues in itself to track her down. A second gave complementary details, enabling her identification as Doris Arthur Jones, the biographer of her father, the forgotten dramatist Henry Arthur Jones. A letter signed Annie proved to be from the mother of 2nd Lieutenant Denis Oliver Barnett (he had perished, aged 20, during The Great War): she had sent the Walkers a copy of her privately published book of his letters from France and Flanders. A tantalising uncaptioned clipping from a Liverpool newspaper, showing some awkward-looking late Victorian men in a garden, was sent by someone named ‘Fran’ and never thrown away.

Were these people socialists, artists and designers, writers or a combination? The most smartly dressed man bears some resemblance to the Liberal politician Joseph Chamberlain, and standing behind him is a man who could be G K Chesterton, but neither are obvious connections for the Walkers – perhaps that was the point of Fran’s comment that the image was ‘priceless’!

I have been privileged to witness the blossoming of the house ‘in synch’ with the changing seasons as the furniture has returned to the rooms, and the objects to the furniture. I have learned a lot that will be useful in my future career and particularly valued the opportunity to be involved in the display of some ‘treasures from the archives’ during an opening event for the neighbours. I am looking forward to studying at UCL, in September, with volunteer colleagues I already know from the Emery Walker cataloguing project.

Dorothy Walker at the Malvern Hotel photographed by G Bernard Shaw (EMW_3_1_1b)

Letter from Violet Gordon-Woodhouse to Dorothy Walker (EMW_3_6_3ci)

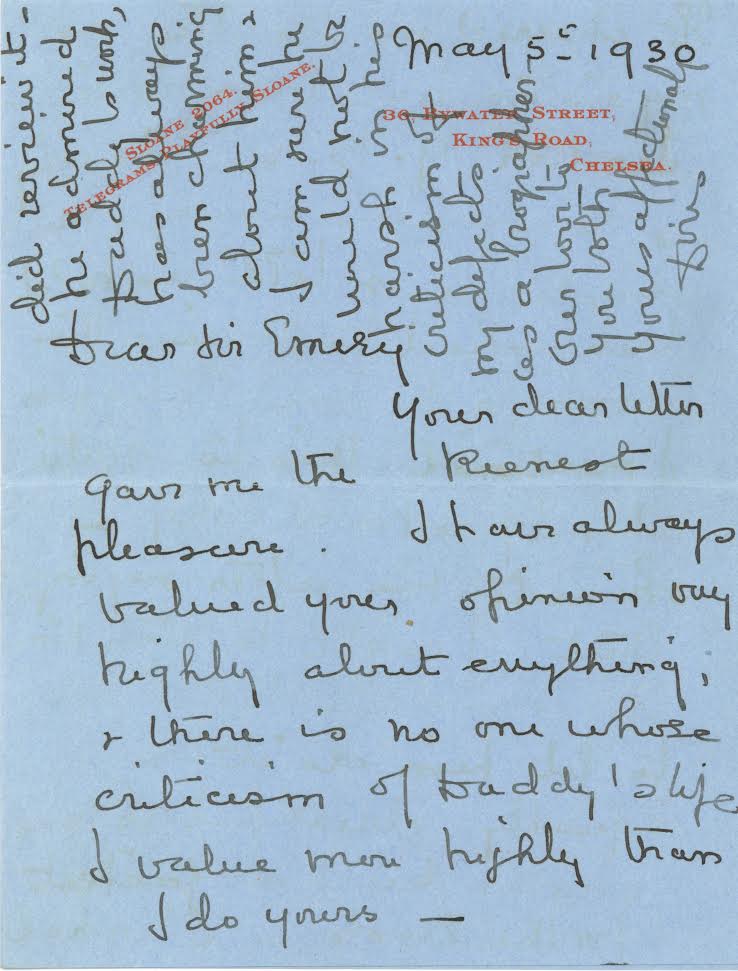

Letter from Doris Arthur Jones to Sir Emery Walker (EMW_4_2_4xia)

Sir Emery Walker with Aiesha the foal at Daneway (EMW_6_9_1a)

An uncaptioned clipping from a Liverpool newspaper. Why did Fran send it? Who were these men? One of the many riddles of the archives. If you know the answer, please let us know!