Archive Volunteer, Molly Richards, is part of the team archiving the Papers of Sir Emery Walker, Engraver, Photographer, Printer, Typographer. Some great treasures have been uncovered in the archive – which you can soon discover for yourself as the Papers of Sir Emery Walker, Engraver, Photographer, Printer, Typographer will soon be available as a digital resource on www.emerywalker.org.uk.

Elizabeth de Haas played a very important part in the history of Emery Walker’s House and it was thanks to her that the Emery Walker Trust was formed in 1999. In this blog however, Molly looks at the life of Elizabeth de Haas before 7 Hammersmith Terrace…

I thought I had a pretty good understanding of Elizabeth de Haas: she moved from Holland to 7 Hammersmith Terrace in 1948 as Dorothy Walker’s companion and stayed beside the Thames until her death in 1999, befriending the movers and shakers in the Arts and Crafts world, caring for the house and establishing the Emery Walker Trust along the way.

Elizabeth de Haas

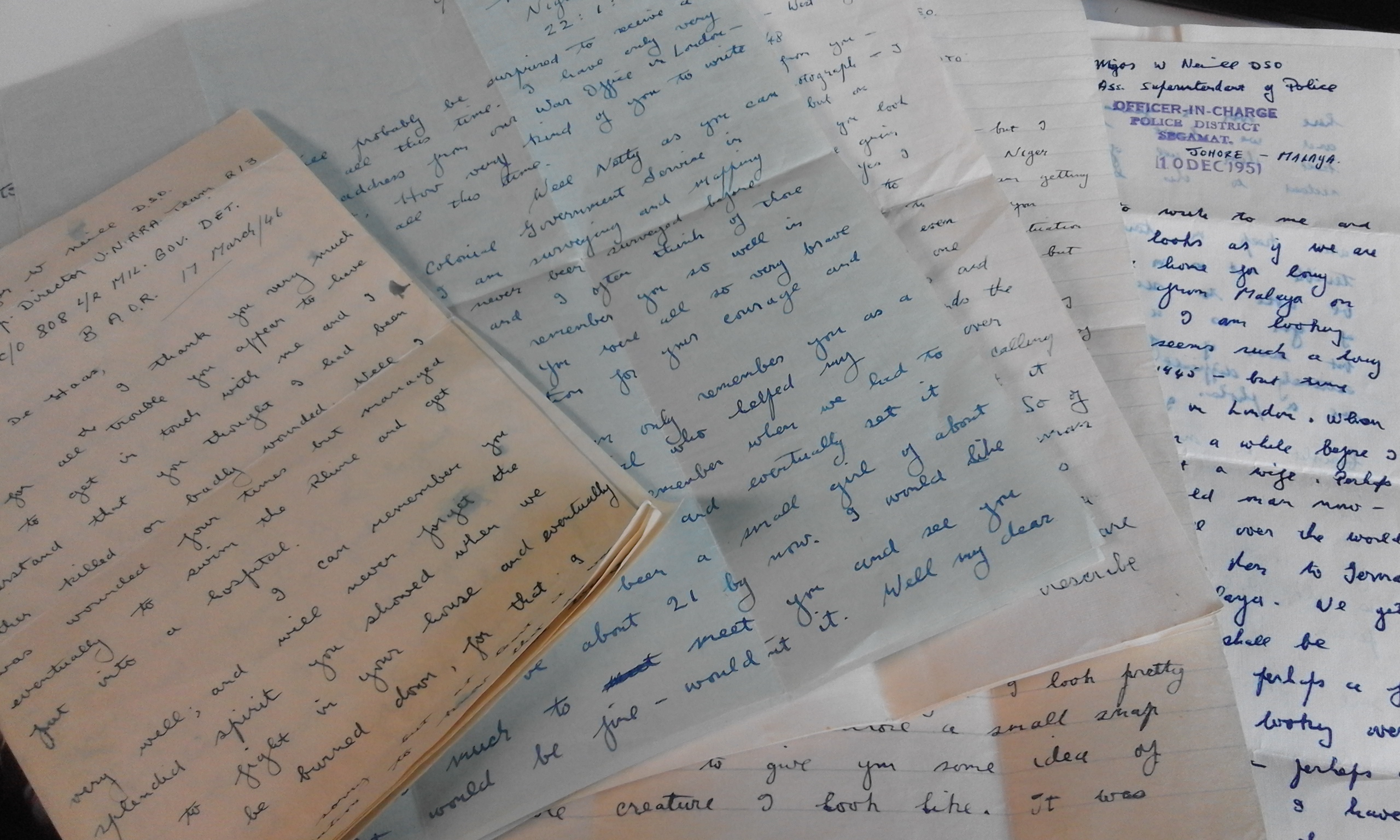

I’d never really thought about Elizabeth’s life before Hammersmith Terrace and so I was intrigued when I came across a bundle of letters that shed some light on her life in wartime Holland.

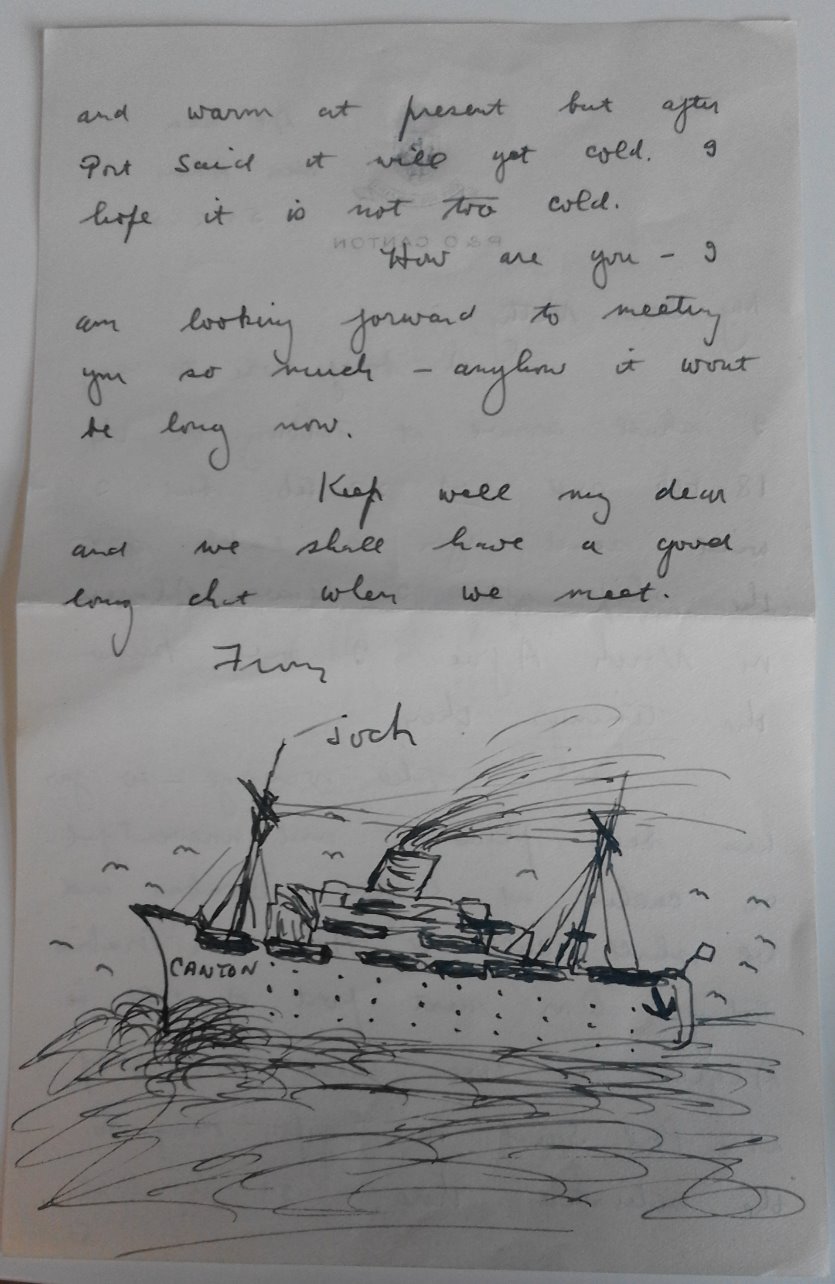

Jock’s letters to Elizabeth

These letters are from a British soldier, Major William Neill – although early on in their correspondence he insists that Elizabeth call him ‘Jock’ as all his friends do. His letters reveal that he met Elizabeth during the Battle of Arnhem in September 1944 and has remembered her ‘splendid spirit,’ ‘courage’ and ‘devotion’ ever since.

From the letters, which date from March 1946 to February 1952, Elizabeth’s experience of the battle can be pieced together: while she and others were ‘consigned to the cellar’ of her house with ‘very little food and water,’ Jock and his soldiers ‘had to fight the Germans in your house.’ Ultimately, Jock was forced to ‘set [the house] on fire’ – but not before he witnessed Elizabeth ‘trying to retrieve some underclothes,’ which she sadly ‘lost…because Germans managed to get into your house.’ Following the fighting, Jock gratefully recalls Elizabeth ‘assisting to nurse and look after my wounded soldiers…without any concern for your own safety’. Indeed, the battle did leave its mark on Elizabeth, even if only temporarily: towards the end of his first letter, Jock writes ‘I hope you can hear all right; I remember when I left you were deaf from bomb blast.’

It is Elizabeth who tracks down Jock in the years following the war and initiates their correspondence. The first thing Jock writes is ‘I thank you very much for all the trouble you appear to have taken to get in touch’ before assuring her that, contrary to her fears, he has not been ‘killed’ or ‘badly wounded’. I often found myself smiling at the gentle flirtations of the letters – a 33 year-old Jock jokes that his chances of finding a wife are slim as he is ‘nearly an old man!!!’ When sending Elizabeth a photograph of himself, he laments that ‘I am not nearly so good-looking’ as during the war, and he teases, when planning a trip to Holland, ‘I am going to be selfish and want you all to myself…if you have a fiancé you can leave him behind for a week until I leave.’

Photograph sent by Jock. On the reverse he has written ‘A terrible picture’

Jock is clearly keen to meet again; he tells Elizabeth he is due at Tilbury Docks on 18th February 1952 and asks her to meet him. Whether they met and continued their correspondence, I know not – the last of the letters I have found is dated early February 1952.

Clearly there was far more to Elizabeth de Haas than just her time at Hammersmith Terrace.

Jock’s final letter, sent en route to Tilbury Docks and illustrated with the Canton ship